Sugar is a controversial word – what was once a staple in our modern diet is now a pretty hairy word that embodies both fear and misunderstanding. So how did we get to this place? To answer that would make this piece a very long read, so perhaps a better question is “Why is everybody so confused?” To start with, sugar doesn’t just come in one form; in fact, there are many. And of these many forms, no two sugars digest, absorb and assimilate in the same way.

Despite the fact we see and hear sugar being negatively touted everywhere we look, this pessimistic message is perhaps a little too narrow-minded. Given the various types of sugar found in various foods we eat, every article demonising sugar surely can’t be referring to every type of sugar… right?

“No two sugars are the same, period.“

A quick chemistry lesson

Sugar can be more specifically classified as either simple, or complex. Simple sugars are made up of singular sugar molecules. This group of single sugars is also referred to as monosaccharides, ‘mono’ meaning one and ‘saccharide’ meaning sugar. There are only three monosaccharides:

1. Glucose – ‘blood sugar’ the body’s preferred fuel source for energy.

2. Fructose – naturally occurring sugar found in fruit and honey.

3. Galactose – naturally occurring sugar found in mammalian milk.

Beyond these three, chemically-speaking, sugar starts getting a lot more complicated. Glucose, (one of the simple sugars and the producer of the body’s energy currency) joins hands with another monosaccharide (fructose or galactose) via a reaction that causes these two simple sugar molecules to bond. Depending on which simple sugar molecule glucose chooses to bond with, and how many bonds are made, determines the type of sugar produced. I know, it’s complicated.

So What Do I Actually Need to Know?

No two sugars are the same, period. When we think of the word sugar, it’s likely the crystalline white substance comes to the forefront. This form of sugar is called sucrose and is made up of a combination of glucose and fructose. While sucrose only contains two monosaccharides, the longer the chain of sugar molecules forged together by bonds, the harder the more complex the type of sugar becomes to digest, absorb and assimilate in the body, but this isn’t a bad thing. Throwing all forms of sugar together in the one basket is not only confusing, but misleading.

Setting the Record Straight

It’s true, our bodies don’t need sugar (recall that white crystalline substance we named sucrose), but they do need glucose. Yes, our bodies can break down our other macronutrients; protein and fat for energy, but it can only do so for short periods of time– glucose is the body’s preferred source of energy. Perhaps it’s for this reason that all types of sugar begin with a singular molecule of glucose. You just can’t argue with science! Regardless of how complex and long sugar molecules get, they all, always begin with glucose, that bonds with something else.

What about fruit?

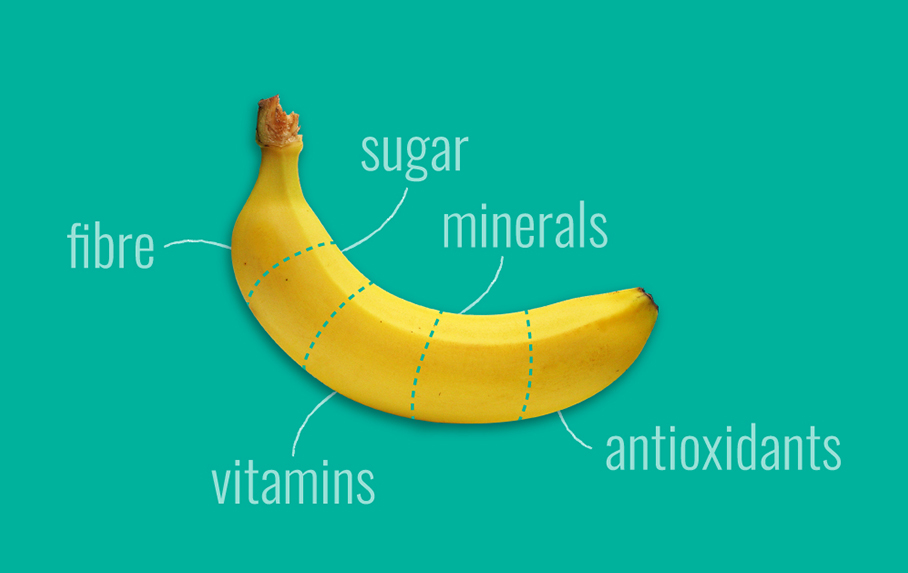

Certain sugar-free folk have risen the argument that it’s not sugar as a whole that should be feared, but specifically fructose (recall the form of sugar found within fruit). This argument has been formed on the basis that fructose places its metabolic burden (the way in which it breaks down) on the liver. Approximately half of fructose is metabolised within the liver and then converted into glucose, allowing rapid absorption and utilisation by the body. The other half is absorbed within the small intestine. If fructose is consumed in excess of glucose, it can be malabsorbed and may cause a rise in triglyceride (fatty acid) production. While these facts are true, fruit does not only contain fructose, it also contains fibre!

Fibre slows down the liver’s absorption and metabolism of fructose, allowing it to reach the bloodstream more slowly. Fibre provides the most benefit when its cell walls remain intact– this highlights the importance and relevance of eating whole fruits, as opposed to fruit juice. The fibre found within fruit acts like an invisible cloak within the digestive tract and liver, shielding these organs from any perceived harm, allowing them to first become acquainted, before settling in and eliciting their full effects within the body.

Fibre also helps the body feel full and satisfied, by triggering the body’s satiety hormones as it digests. Additionally, fibre acts as fuel for the digestive system, positively affecting the colonisation of beneficial bacteria to thrive within the stomach and intestines. Fibre-rich fruit also contains a plethora of vitamins and minerals, is incredibly hydrating and rich in antioxidants.

A recent study by the University of Canberra put sugar to the test – the study examines the comparison of data concerning the metabolism and therefore impact of glucose, fructose and sucrose. The results of the study reveal that fructose should not be demonised– fructose was found to have no effect whatsoever on fasting blood glucose, insulin and triglyceride levels when switched with glucose and sucrose. This same study also highlights the link between various health conditions and high sugar intake, but notes that fructose-derived sugars are a ‘better choice’.

“When it comes to sugar intake, take what

you read with a grain of salt– not all sugars

are created equal.”

So What’s the Take-Home Message?

When it comes to sugar intake, take what you read with a grain of salt – not all sugars are created equal. Whole food sources of sugar, like fruit are healthy choices that do not negatively affect the metabolism, or overall health. Fruit is full of fibre, which positively influences digestion, gut flora and satiety. When choosing to add a little sweetness to your life, fruit is a better choice.But as with all good things, should be consumed in moderation, alongside an active lifestyle.

REFERENCES

Challenging the Fructose Hypothesis: New Perspectives on Fructose Consumption and Metabolism

Metabolic effects of dietary fructose

Examining the Health Effects of Fructose

Sex, Body Mass Index, and Dietary Fiber Intake Influence the Human Gut Microbiome